Peggy Noel

April 25, 2014Traveling a few miles out of Gettysburg to the West on Fairfield Road you cross a small bridge over Marsh Creek. The slow moving water winds slowly off to the left along Gettysburg Campground creating a rather picturesque scene. This quiet area, however, holds a rather tragic tale… the tale of Peggy Noel, that has been told and retold for many years, going back to the days before the Civil War.

According to the story, a young Gettysburg woman was traveling the road on a dark, snowy night. Peggy Noel was returning home from a trip to Fairfield and was running late. To make up for lost time, the coachman was going too fast for the poor conditions that evening. As they approached the bridge, the horses tripped and fell to the muddy roadway. The driver was thrown to the side of the road. He looked back in horror to see the coach topple and the doors spring open. Peggy Noel was thrown from her coach. She became entangled in the large spoked rear wheel and to the driver’s horror he saw her decapitated. The head of the young woman rolled across the bridge eventually falling into the water below.

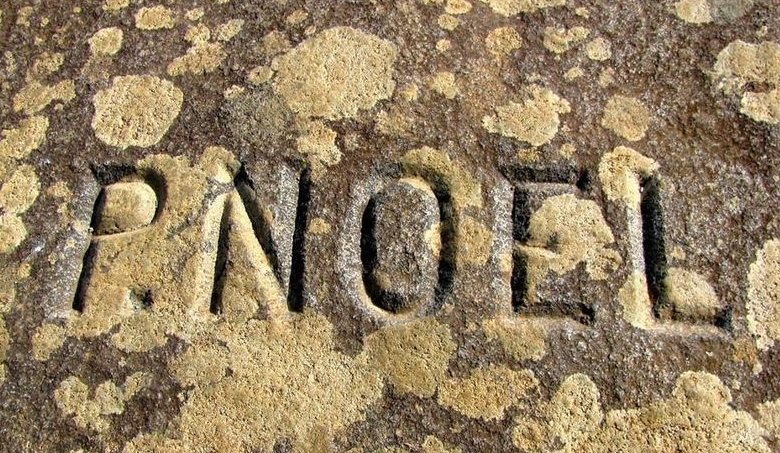

For days they searched the banks of the creek to no avail. Eventually Peggy went to the grave headless. Rumor tells us that the family did not mark the grave. They couldn’t bear the thought of visiting a site of such horror, a grave with a headless corpse. There is a rock out on the battlefield just north of Devil’s Den with the letters P. Noel carved into it. To this day no one knows when it was put there or who did it. Could it be the final resting-place of Peggy Noel?

Along the banks of Marsh Creek, South of Fairfield Road, stories persist of a headless woman wading through the waters. She appears to be searching for something. Could Peggy still be searching for her head, hoping to be again complete!

I had read this story years ago in a local ghost storybook and filed it away in my mind. Imagine my surprise in the summer of 2002, when a family of 4 (Mom, Dad, son of about 17 and daughter, maybe 13), approached me after a Baltimore Street ghost tour. The son acted as the spokesman for the group. He said that he had a silly question for me about a ghost story. I told him that the only silly questions are those that don’t get asked and I’d be happy to hear his. That is when he surprised me by saying that the family had arrived in Gettysburg a few days earlier and had taken some historical tours but my tour was their first adventure into the spirit world. As he spoke, I could see that the mother was very uncomfortable with the whole situation. I then found out why. He went on to ask if I knew stories concerning a headless woman in the vicinity of Gettysburg Campground out on Fairfield Road. As I started to search the recesses in my mind, I asked out of curiosity, Why?

It seems on that very morning, his mother had awakened just before dawn. They were staying at a campsite along Marsh Creek just off Fairfield Road. The mother decided to go out in the fresh morning air and walk to the restrooms. Rather than return directly to the camper, she took a longer way back, walking along the edge of the creek in the morning air.

It wasn’t long after that, the mother awakened the rest of the family as she came screaming and crying into the camper. It took them 15-20 minutes to calm her down to the point that she could tell her tale.

(To be Continued)

Regimental Flank Markers

March 13, 2014

Located throughout the battlefield and often mistaken for graves, these small, rectangular stones are known as regimental flank markers. They are placed on either side of monuments or cannons and note the extreme ends of particular regiments or batteries. Engraved with the regimental/battery name and number and bearing the letter R or L (or sometimes RF or LF), these markers will assist the visitor to visualize the line that was formed by that unit. Fighting, in lines, shoulder to shoulder these stones tell you how far the line stretched and which direction the men were facing. Quite frequently the stones for different units will be found right next to each other on the field. For example, the right flank marker for one unit will stand directly next to the left flank marker of its neighbor in line helping one better grasp the infantry and artillery tactics of the 19th Century.

Castle at Little Round Top

September 10, 2013 The “castle” on Little Round Top is always a favorite of visitors to the battlefield. Dedicated on July 3, 1893 at a cost of almost $11,000.00 it is without question the largest & most expensive regimental monument on the field.

The “castle” on Little Round Top is always a favorite of visitors to the battlefield. Dedicated on July 3, 1893 at a cost of almost $11,000.00 it is without question the largest & most expensive regimental monument on the field.

The memorial represents the 44th New York & (2) companies from the 12th New York Infantry Regiments & as is the case with most of the monuments the castle has a story to tell – the dimensions of the monument were purposely designed to reflect the numeric designations of the units it represents. The tower is 44 feet high & the interior chamber is 12 feet square.

There is an observation deck which can be reached by climbing a circular staircase inside.

Bronze plaques found inside the chamber contain a complete muster roll for each company of the regiment.

This memorial was designed by Union General Daniel Butterfield who also adapted the music for “Taps” for his Brigade (the Third), First Division, Fifth Army Corps, Army of the Potomac in July, 1862.

The 44th New York was raised as a memorial to Ephraim Elmer Ellsworth who was the first Union officer killed during the war.

1st Delaware Monument

August 16, 2013 The State of Delaware supplied two regiments for the Union at the Battle of Gettysburg. One of these, the 1st Delaware, had the opportunity to spearhead a counter-charge on July 3rd as the the attack of General Pickett faltered at the wall these men were defending. This counter-assault by the men from Delaware resulted in the capture of several Confederate battle flags & many prisoners. The Battle of Gettysburg was to cost this unit 77 casualties & at battle’s end they were led by a lieutenant who was the highest ranking officer left. Their memorial was dedicated on June 10, 1886 & may be found on Hancock Avenue at the wall over which they charged that July day 150 years ago.

The State of Delaware supplied two regiments for the Union at the Battle of Gettysburg. One of these, the 1st Delaware, had the opportunity to spearhead a counter-charge on July 3rd as the the attack of General Pickett faltered at the wall these men were defending. This counter-assault by the men from Delaware resulted in the capture of several Confederate battle flags & many prisoners. The Battle of Gettysburg was to cost this unit 77 casualties & at battle’s end they were led by a lieutenant who was the highest ranking officer left. Their memorial was dedicated on June 10, 1886 & may be found on Hancock Avenue at the wall over which they charged that July day 150 years ago.

Charlie Weaver’s Carvings on Display

June 24, 2013Charlie Weaver’s Carvings On display at:

Soldiers National Museum

777 Baltimore Street

Gettysburg, PA 17325

Who was Charlie Weaver?

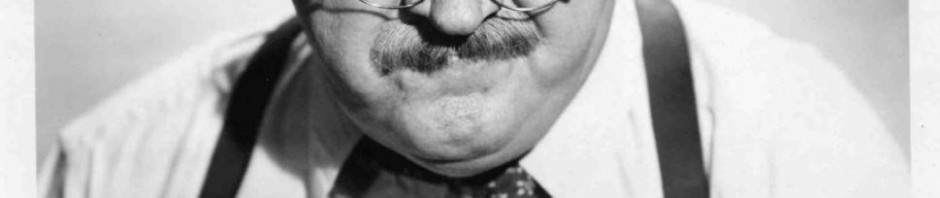

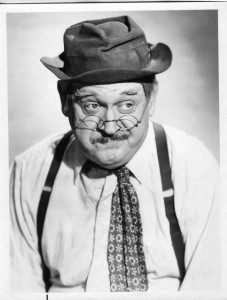

Clifford Charles Arquette

(12/27/1905 – 10/23/1974)

Cliff, born in Toledo, Ohio was a comedian, actor, pianist, composer, songwriter, wood carver and Civil War buff; however, he was best known for his role as Charlie Weaver.

His family got their start in show business largely due to his career (His son Lewis, and his grandchildren Patricia, Rosanna, Alexis, Richmond, and David Arquette).

Cliff Arquette’s Soldiers Museum opened in Gettysburg in 1959.

Due to professional obligations in California, he sold the museum to Leroy Smith who continued operating it as Charlie Weaver’s American Museum of the Civil War with Cliff’s blessing.

These carvings are a selection of the 57 figures that Charlie did.

For Charlie, it was a labor of love, requiring 25 years of research and careful work to ensure that everything about the figures was perfectly reproduced.

He made them entirely by hand starting by sawing the white pine block, down to every last stitch in the uniforms.

Charlie made all of the accessories, including making custom molds to cast each of the trigger plates and hammerlocks on the painstakingly reproduced guns.

Abraham Lincoln: Did Lack of Security Lead to his Death?

February 8, 2013 Abraham Lincoln, who was assassinated in April of 1865, was the first American president to be killed in office.

Abraham Lincoln, who was assassinated in April of 1865, was the first American president to be killed in office.

In some ways, his murder came as no surprise. There was no Secret Service at the time and he’d been receiving death threats since he was first elected, and the nation was at war with itself.

The one man assigned to protect the president at Ford’s Theatre that fateful night, John Frederick Parker, was not at his post during the show. He spent some of his time watching the show from a different part of the theatre and spent the intermission at the saloon next door, which is where he was found when the president was shot.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t unexpected. Presidential security was, at the time, scattered at best and hampered by Lincoln himself.

There were elaborate security precautions at the inauguration but they were quickly dropped for Lincoln’s first term—at his insistence.

Republican Inaugural visitor from Iowa, Charles Aldrich, wrote about the March 4, 1861 event:

I went across the street… The area in front of this northeast corner of the Capitol was filled with spectators to the number of many thousands. Just before the appearance of Mr. Lincoln, a file of soldiers, doubtless regulars, came into the area, and marched along in front of the platform, slowly making their way through the crowd. From where I stood I could see their bayonets above the heads of the people. There was at that time serious apprehension that the President might be shot when he appeared to make his address, but this small company of men was all that was in sight in the way of defense. It was quietly understood, however, that several hundred men were scattered through the crowd armed with revolvers.

But shortly thereafter, even the mounted and foot guards posted at the White House gates were dismissed.

In late 1862, two companies were assigned to protect the President — the Union Light Guard of cavalry from Ohio and the 150th Pennsylvania Regiment of infantry- at the insistence of various military leaders.

The special cavalry division, the “bucktails”, were assigned to escort Lincoln, who was prone to riding alone. Their efforts were met with marginal success.

Lincoln rode particularly often between the White House and the “Soldier’s Home”, an area in the Northeast part of the city, that was country-like and where the Lincolns had a small cottage. It was approximately a three-mile ride. He also changed his travel schedule at will.

Lincoln also frequently walked from the White House to the War Department—where the staff was under strict orders to make sure that he was escorted home.

In August of 1864, while Lincoln was riding to Soldier’s Home, he was fired upon. The shot startled his horse, which bolted, causing Lincoln to lose his hat.

It also forced Lincoln to take security more seriously, and allow for both a police guard and to accept the cavalry escorts.

It wasn’t until November, 1864 that the police force in Washington, D.C. created a four man team to act as private body guards to the president.

John Frederick Parker was one of those men. And his actions that fateful day in April let down a man, and a nation, struggling for security.

The Oldest Union Commander

November 20, 2012The Civil War brought this military man out of retirement—25 years later!

General George Sears Greene lived a fascinating life—he might just be the most interesting Civil War figure that you’ve never heard of. Second in his class at West Point, he stayed on for four years as an assistant professor in mathematics and engineering, and his students included a certain cadet named Robert E. Lee. In 1836, Greene retired from the army and that was the end of his military career…until 1862.

General Greene was 62 when the crisis of the Civil War drove him to re-enlist, making him the oldest Union commander in the Army of the Potomac. “Pap Greene,” as they sometimes called him, led with an aggressiveness that surprised many, and he applied the ingenuity that had brought him success as a civil engineer. The pinnacle of his military career was the Battle of Gettysburg: Greene and his command of 1,350 New York soldiers defended the peak of Culp’s Hill against Confederate troops that outnumbered them 3 to 1.

That was when Greene’s civil engineering influences proved not just beneficial, but decisive in the outcome of the battle. Prior to the confrontation, he insisted that his men prepare by building strong fortifications on the field of battle—an idea that his superiors showed no interest in. Those fortifications allowed Greene and his regiment to hold off multiple attacks and defend the vital Union supply line that ran along the Baltimore Pike behind them. Greene’s stand played a crucial, but often underestimated, role in the Battle of Gettysburg.

After the War, Greene returned to civil engineering and is remembered as one of the founding members of the American Society of Civil Engineers and Architects. He died just shy of the turn of the century, at the age of 97. A 2-ton boulder was transported from Culp’s Hill to Greene’s grave in Warwick, Rhode Island, where it marks his burial spot. On September 26, 1907, the State of New York honored General Greene with a portrait statue on the Gettysburg Battlefield, which you can find atop Culp’s Hill, gazing down the slopes that Greene once defended.

The Gettysburg Battlefield is home to an incredible number of breathtaking monuments and memorials! Read about some of them here!

The Lonely Mural

August 15, 2012What if we told you there was a Gettysburg memorial worth a quarter of a million dollars–$250,000!–and that you’ve probably never seen it? Would you believe us? Well, it’s true! And unless you’re a diehard Gettysburg groupie, chances are that you haven’t even heard of it.

The Coster Avenue Mural in Gettysburg was designed by artist, historian, and Civil War descendant Mark H. Dunkelman, who painted it with the assistance of mural master Johan Bjurman. Dedicated on the 125th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, the mural depicts the clash between Union Colonel Charles R. Coster’s forces (27th Pennsylvania, 134th & 154th New York Regiments) and the Confederates led by Brigadier General Harry Hays & Colonel Isaac Avery.

Coster’s Brigade made their stand behind a fence-line in Kuhn’s Brickyard, taking what little shelter they could from the wooden fence posts, but mostly exposed to enemy fire. The Confederates, who far outnumbered the Union soldiers, descended upon the fence so quickly that Coster’s men only had time to fire six to nine shots each before the fight broke into clusters of hand-to-hand combat. Confederate forces overwhelmed the smaller contingent of Union soldiers, taking many of them prisoner and pursuing others nearly to Cemetery Hill. All told, it was a brief, brutal assault that took the lives of 563 of Coster’s men, while the Confederates lost 200 of their own.

National Park personnel report that Coster Avenue, the site of this breathtaking mural and monument, is the least visited portion of the battlefield. Overlooked, unknown, and often alone, it’s a sad truth that this memorial to American soldiers is not often remembered.

Will you be the exception? Will you remember the forgotten soldiers, who fought and died in Gettysburg?

The Amos Humiston Memorial

June 20, 2012On July 1, 1863, an unidentified young soldier of the Union Army was mortally wounded on the Gettysburg Battlefield. Dying, he clung to the only memento he possessed–an ambrotype (a kind of photograph) of his three small children. We don’t know what he experienced in those final moments, but in one of his final letters he composed a heart-wrenching poem that expressed how deeply he missed his family (published in 1999 in Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier). With his thoughts dwelling upon them, he breathed his last…and that’s where the story begins.

A local girl discovered the ambrotype in the soldier’s hand and took it to a local tavern, where Dr. J. Francis Bournes saw it and took up the cause of finding the now-bereaved family. She sent a description of the children in the picture to the newspaper (they didn’t have the technology to reprint the image yet) and the story swept across the Union. Copies of the image were made and sold for charity as everyone searched for the family.

The story found its way to the American Presbyterian, a church publication, in Portville, New York, where Phylinda Humiston happened to read it. It was October, and her husband had not sent a letter since the Battle of Gettysburg–she feared the worst. She contacted Dr. Bournes, who sent her a copy of the ambrotype, and then Mrs. Humiston positively identified her three children, Franklin, Alice, and Frederick, as those in the picture. The unknown soldier had a name: Sergeant Amos Humiston.

Dr. Bournes made a special trip to NY to return the original ambrotype to Amos’ widow and children. The story had become so famous that there was an outpouring of sympathy donations, which were used to establish a Soldiers’ Orphans’ Home in Gettysburg in 1866. Mrs. Humiston moved to Gettysburg to serve as the first matron of the orphanage, Amos’ body was moved to the Gettysburg National Cemetery, and a monument now marks the spot where he died. You can visit it on Stratton Street, beside the firehouse.

The End

…or is it? Phylinda’s successor was not as kind-hearted to orphans– learn more about the horrific abuses Rosa Carmichael brought upon the orphanage and tour the dungeons today!

Hike with Ike

May 11, 2012Hiking and storytelling have always gone hand-in-hand, so we know you’ll love this guided walking tour of downtown Gettysburg! And did we mention it’s free? Meet a Park Ranger at the Gettysburg College gates (the corner of North Washington and Water Streets) and prepare for an enthralling adventure! The hikes will be offered weekly on Thursdays at 7:15 PM, starting June 14th through August 16th.

Call 717-338-9114 or visit www.nps.gov/eise today for more information!